I have long promised that Hare would not have multi-threading, and it seems that I have broken that promise. However, I have remained true to the not-invented-here approach which is typical of my style by introducing it only after designing an entire kernel to implement it on top of.1

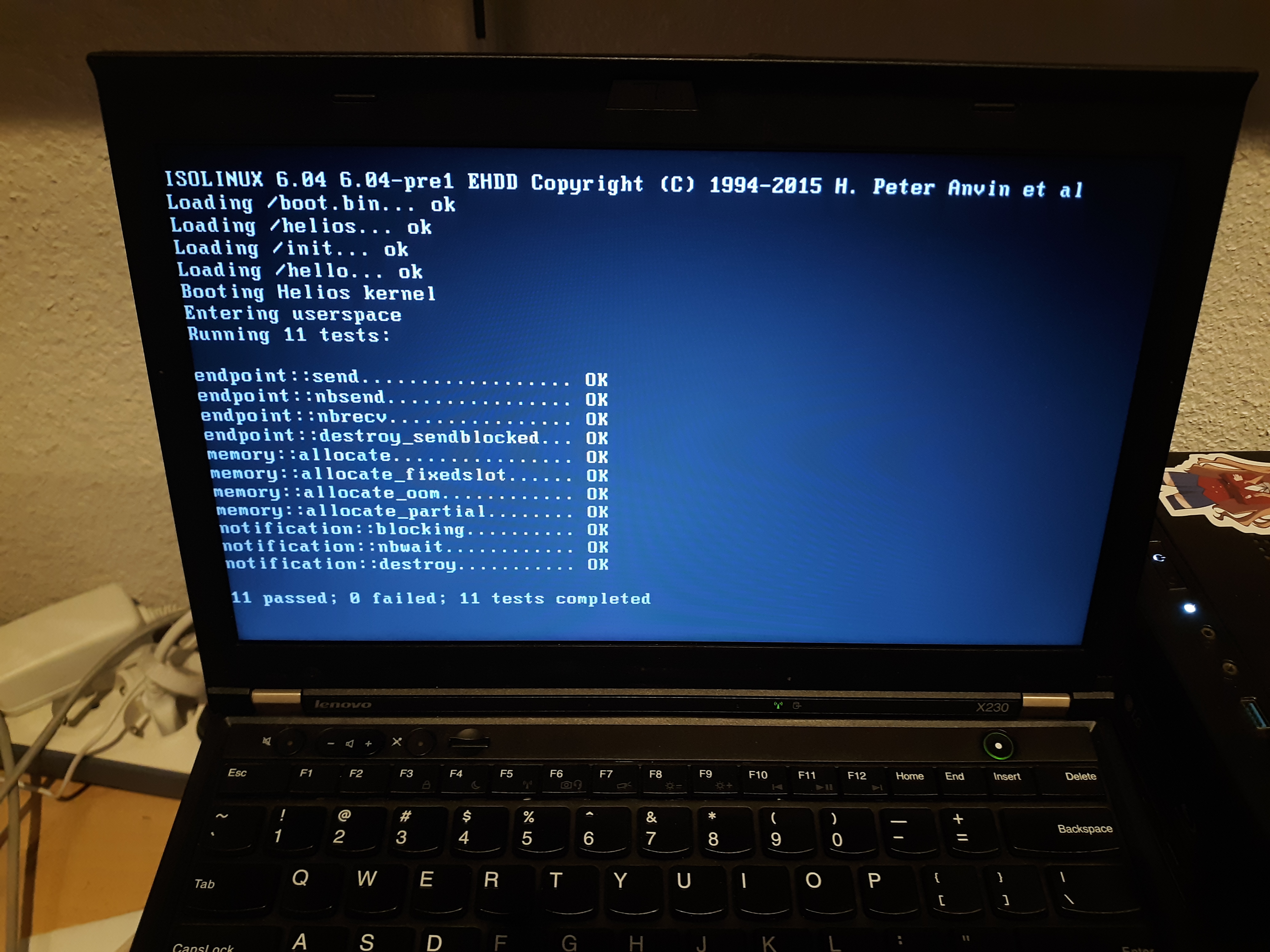

For some background, Helios is a micro-kernel written in Hare. In addition to the project, the Vulcan system is a small userspace designed to test the kernel.

While I don’t anticipate multi-threaded processes playing a huge role in the complete Ares system in the future, they do have a place. In the long term, I would like to be able to provide an implementation of pthreads for porting existing software to the system. A more immediate concern is how to test the various kernel primitives provided by Helios, such as those which facilitate inter-process communication (IPC). It’s much easier to test these with threads than with processes, since spawning threads does not require spinning up a new address space.

@test fn notification::wait() void = {

const note = helios::newnote()!;

defer helios::destroy(note)!;

const thread = threads::new(¬ification_wait, note)!;

threads::start(thread)!;

defer threads::join(thread)!;

helios::signal(note)!;

};

fn notification_wait(note: u64) void = {

const note = note: helios::cap;

helios::wait(note)!;

};

So how does it work? Let’s split this up into two domains: kernelspace and userspace.

Threads in the kernel

The basic primitive for threads and processes in Helios is a “task”, which is simply an object which receives some CPU time. A task has a capability space (so it can invoke operations against kernel objects), an virtual address space (so it has somewhere to map the process image and memory), and some state, such as the values of its CPU registers. The task-related structures are:

// A task capability.

export type task = struct {

caps::capability,

state: uintptr,

@offset(caps::LINK_OFFS) link: caps::link,

};

// Scheduling status of a task.

export type task_status = enum {

ACTIVE,

BLOCKED, // XXX: Can a task be both blocked and suspended?

SUSPENDED,

};

// State for a task.

export type taskstate = struct {

regs: arch::state,

cspace: caps::cslot,

vspace: caps::cslot,

ipc_buffer: uintptr,

status: task_status,

// XXX: This is a virtual address, should be physical

next: nullable *taskstate,

prev: nullable *taskstate,

};

Here’s a footnote to explain some off-topic curiosities about this code: 2

The most interesting part of this structure is arch::state, which stores the task’s CPU registers. On x86_64,3 this structure is defined as follows:

export type state = struct {

fs: u64,

fsbase: u64,

r15: u64,

r14: u64,

r13: u64,

r12: u64,

r11: u64,

r10: u64,

r9: u64,

r8: u64,

rbp: u64,

rdi: u64,

rsi: u64,

rdx: u64,

rcx: u64,

rbx: u64,

rax: u64,

intno: u64,

errcode: u64,

rip: u64,

cs: u64,

rflags: u64,

rsp: u64,

ss: u64,

};

This structure is organized in part according to hardware constraints and in part at the discretion of the kernel implementer. The last five fields, from %rip to %ss, are constrained by the hardware. When an interrupt occurs, the CPU pushes each of these registers to the stack, in this order, then transfers control to the system interrupt handler. The next two registers serve a special purpose within our interrupt implementation, and the remainder are ordered arbitrarily.

In order to switch between two tasks, we need to save all of this state somewhere, then load the same state for another task when returning from the kernel to userspace. The save/restore process is handled in the interrupt handler, in assembly:

.global isr_common

isr_common:

_swapgs

push %rax

push %rbx

push %rcx

push %rdx

push %rsi

push %rdi

push %rbp

push %r8

push %r9

push %r10

push %r11

push %r12

push %r13

push %r14

push %r15

// Note: fsbase is handled elsewhere

push $0

push %fs

cld

mov %rsp, %rdi

mov $_kernel_stack_top, %rsp

call arch.isr_handler

_isr_exit:

mov %rax, %rsp

// Note: fsbase is handled elsewhere

pop %fs

pop %r15

pop %r15

pop %r14

pop %r13

pop %r12

pop %r11

pop %r10

pop %r9

pop %r8

pop %rbp

pop %rdi

pop %rsi

pop %rdx

pop %rcx

pop %rbx

pop %rax

_swapgs

// Clean up error code and interrupt #

add $16, %rsp

iretq

I’m not going to go into too much detail on interrupts for this post (maybe in a later post), but what’s important here is the chain of push/pop instructions. This automatically saves the CPU state for each task when entering the kernel. The syscall handler has something similar.

This suggests a question: where’s the stack?

Helios has a single kernel stack,4 which is moved to %rsp from $_kernel_stack_top in this code. This is different from systems like Linux, which have one kernel stack per thread; the rationale behind this design choice is out of scope for this post.5 However, the “stack” being pushed to here is not, in fact, a traditional stack.

x86_64 has an interesting feature wherein an interrupt can be configured to use a special “interrupt stack”. The task state segment is a bit of a historical artifact which is of little interest to Helios, but in long mode (64-bit mode) it serves a new purpose: to provide a list of addresses where up to seven interrupt stacks are stored. The interrupt descriptor table includes a 3-bit “IST” field which, when nonzero, instructs the CPU to set the stack pointer to the corresponding address in the TSS when that interrupt fires. Helios sets all of these to one, then does something interesting:

// Stores a pointer to the current state context.

export let context: **state = null: **state;

fn init_tss(i: size) void = {

cpus[i].tstate = taskstate { ... };

context = &cpus[i].tstate.ist[0]: **state;

};

// ...

export fn save() void = {

// On x86_64, most registers are saved and restored by the ISR or

// syscall service routines.

let active = *context: *[*]state;

let regs = &active[-1];

regs.fsbase = rdmsr(0xC0000100);

};

export fn restore(regs: *state) void = {

wrmsr(0xC0000100, regs.fsbase);

const regs = regs: *[*]state;

*context = ®s[1];

};

We store a pointer to the active task’s state struct in the TSS when we enter userspace, and when an interrupt occurs, the CPU automatically places that state into %rsp so we can trivially push all of the task’s registers into it.

There is some weirdness to note here: the stack grows downwards. Each time you push, the stack pointer is decremented, then the pushed value is written there. So, we have to fill in this structure from the bottom up. Accordingly, we have to do something a bit unusual here: we don’t store a pointer to the context object, but a pointer to the end of the context object. This is what &active[-1] does here.

Hare has some memory safety features by default, such as bounds testing array accesses. Here we have to take advantage of some of Hare’s escape hatches to accomplish the goal. First, we cast the pointer to an unbounded array of states — that’s what the *[*] is for. Then we can take the address of element -1 without the compiler snitching on us.

There is also a separate step here to save the fsbase register. This will be important later.

This provides us with enough pieces to enter userspace:

// Immediately enters this task in userspace. Only used during system

// initialization.

export @noreturn fn enteruser(task: *caps::capability) void = {

const state = objects::task_getstate(task);

assert(objects::task_schedulable(state));

active = state;

objects::vspace_activate(&state.vspace)!;

arch::restore(&state.regs);

arch::enteruser();

};

What we need next is a scheduler, and a periodic interrupt to invoke it, so that we can switch tasks every so often.

Scheduler design is a complex subject which can have design, performance, and complexity implications ranging from subtle to substantial. For Helios’s present needs we use a simple round-robin scheduler: each task gets the same time slice and we just switch to them one after another.

The easy part is simply getting periodic interrupts. Again, this blog post isn’t about interrupts, so I’ll just give you the reader’s digest:

arch::install_irq(arch::PIT_IRQ, &pit_irq);

arch::pit_setphase(100);

// ...

fn pit_irq(state: *arch::state, irq: u8) void = {

sched::switchtask();

arch::pic_eoi(arch::PIT_IRQ);

};

The PIT, or programmable interrupt timer, is a feature on x86_64 which provides exactly what we need: periodic interrupts. This code configures it to tick at 100 Hz and sets up a little IRQ handler which calls sched::switchtask to perform the actual context switch.

Recall that, by the time sched::switchtask is invoked, the CPU and interrupt handler have already stashed all of the current task’s registers into its state struct. All we have to do now is pick out the next task and restore its state.

// see idle.s

let idle: arch::state;

// Switches to the next task.

export fn switchtask() void = {

// Save state

arch::save();

match (next()) {

case let task: *objects::taskstate =>

active = task;

objects::vspace_activate(&task.vspace)!;

arch::restore(&task.regs);

case null =>

arch::restore(&idle);

};

};

fn next() nullable *objects::taskstate = {

let next = active.next;

for (next != active) {

if (next == null) {

next = tasks;

continue;

};

const cand = next as *objects::taskstate;

if (objects::task_schedulable(cand)) {

return cand;

};

next = cand.next;

};

const next = next as *objects::taskstate;

if (objects::task_schedulable(next)) {

return next;

};

return null;

};

Pretty straightforward. The scheduler maintains a linked list of tasks, picks the next one which is schedulable,6 then runs it. If there are no schedulable tasks, it runs the idle task.

Err, wait, what’s the idle task? Simple: it’s another state object (i.e. a set of CPU registers) which essentially works as a statically allocated do-nothing thread.

const idle_frame: [2]uintptr = [0, &pause: uintptr];

// Initializes the state for the idle thread.

export fn init_idle(idle: *state) void = {

*idle = state {

cs = seg::KCODE << 3,

ss = seg::KDATA << 3,

rflags = (1 << 21) | (1 << 9),

rip = &pause: uintptr: u64,

rbp = &idle_frame: uintptr: u64,

...

};

};

“pause” is a simple loop:

.global arch.pause

arch.pause:

hlt

jmp arch.pause

In the situation where every task is blocking on I/O, there’s nothing for the CPU to do until the operation finishes. So, we simply halt and wait for the next interrupt to wake us back up, hopefully unblocking some tasks so we can schedule them again. A more sophisticated kernel might take this opportunity to go into a lower power state, perhaps, but for now this is quite sufficient.

With this last piece in place, we now have a multi-threaded operating system. But there is one more piece to consider: when a task yields its time slice.

Just because a task receives CPU time does not mean that it needs to use it. A task which has nothing useful to do can yield its time slice back to the kernel through the “yieldtask” syscall. On the face of it, this is quite simple:

// Yields the current time slice and switches to the next task.

export @noreturn fn yieldtask() void = {

arch::sysret_set(&active.regs, 0, 0);

switchtask();

arch::enteruser();

};

The “sysret_set” updates the registers in the task state which correspond with system call return values to (0, 0), indicating a successful return from the yield syscall. But we don’t actually return at all: we switch to the next task and then return to that.

In addition to being called from userspace, this is also useful whenever the kernel blocks a thread on some I/O or IPC operation. For example, tasks can wait on “notification” objects, which another task can signal to wake them up — a simple synchronization primitive. The implementation makes good use of sched::yieldtask:

// Blocks the active task until this notification is signalled. Does not return

// if the operation is blocking.

export fn wait(note: *caps::capability) uint = {

match (nbwait(note)) {

case let word: uint =>

return word;

case errors::would_block =>

let note = note_getstate(note);

assert(note.recv == null); // TODO: support multiple receivers

note.recv = sched::active;

sched::active.status = task_status::BLOCKED;

sched::yieldtask();

};

};

Finally, that’s the last piece.

Threads in userspace

Phew! That was a lot of kernel pieces to unpack. And now for userspace… in the next post! This one is getting pretty long. Here’s what you have to look forward to:

- Preparing the task and all of the objects it needs (such as a stack)

- High-level operations: join, detach, exit, suspend, etc

- Thread-local storage…

- in the Hare compiler

- in the ELF loader

- at runtime

- Putting it all together to test the kernel

We’ll see you next time!

-

Jokes aside, for those curious about multi-threading and Hare: our official stance is not actually as strict as “no threads, period”, though in practice for many people it might amount to that. There is nothing stopping you from linking to pthreads or calling clone(2) to spin up threads in a Hare program, but the standard library explicitly provides no multi-threading support, synchronization primitives, or re-entrancy guarantees. That’s not to say, however, that one could not build their own Hare standard library which does offer these features — and, in fact, that is exactly what the Vulcan test framework for Helios provides in its Hare libraries. ↩︎

-

Capabilities are essentially references to kernel objects. The kernel object for a task is the taskstate struct, and there can be many task capabilities which refer to this. Any task which possesses a task capability in its capability space can invoke operations against this task, such as reading or writing its registers.

The link field is used to create a linked list of capabilities across the system. It has a doubly linked list for the next and previous capability, and a link to its parent capability, such as the memory capability from which the task state was allocated. The list is organized such that copies of the same capability are always adjacent to one another, and children always follow their parents.

The answer to the XXX comment in task_status is yes, by the way. Something to fix later. ↩︎ -

Only x86_64 is supported for now, but a RISC-V port is in-progress and I intend to do arm64 in the future. ↩︎

-

For now; in the future it will have one stack per CPU. ↩︎

-

Man, I could just go on and on and on. ↩︎

-

A task is schedulable if it is configured properly (with a cspace, vspace, and IPC buffer) and is not currently blocking (i.e. waiting on I/O or something). ↩︎