When Less is More: Database Connection Scaling

Why a high max_connections setting can be detrimental to performance

Introduction

As a PostgreSQL Support Engineer, one common scenario we experience is a slow system on a reasonably powerful machine. In these cases, we often see that max_connections is set to 10,000 or more, sometimes even as high as 30,000. While we will advise that max_connections is too high and needs to be lowered, the usual response is, “Well, most of those connections are idle, so they shouldn’t affect performance.” This statement is not true, as an idle connection is not weightless. In this article, we’ll explore why a high idle connection count can be detrimental to database performance.

The Math

It is natural for a DBA or sysadmin (or an application developer) to configure PostgreSQL for the expected connection load. If, after discussion between teams on a project, the anticipated number of clients on an enterprise application would be 10,000, max_connections = 10000 would get coded into postgresql.conf However, it seems that often times these values are decided by the business and not necessarily by those who have more intimate knowledge of the hardware. For example, in many enterprise data centers, a database server might be provisioned with 128 CPU cores. With hyperthreading on, the machine can handle 256 processes. At EDB, we would typically expect a comfortable load on a core to be around 4 processes. If we put this in a formula, it should look something like this:

max_connections = #cores * 4

In the case of this large enterprise machine, 256 * 4 = 1024, so max_connections should be set to no higher than 1024. Even this value is highly contested in the community, where many experts believe that max_connections should not exceed a few hundred.

“But the connections are all idle!”

While it would be intuitive to think that it would be harmless to set max_connections = 30000 and promise that the vast majority of those connections to be idle, I would encourage proponents of the high max_connections setting to think more deeply about the implications of having so many connections. In particular, we must recall that PostgreSQL is a process-based application, which means that the underlying operating system needs to perform context switches to run queries and perform the underlying interfacing with hardware. On particularly busy systems with high CPU counts there’s risk of being affected by cache line contention, which I previously wrote about

Even if the operating system could handily manage thousands of processes simultaneously, Postgres’ supervisor process (i.e., postmaster) needs to keep tabs on each process/backend it has forked because of an incoming connection. This management done by postmaster is can become expensive, as non-idle queries require postmaster to get a snapshot of what’s visible/invisible, committed/uncommitted (aka, Transaction Isolation), and that requires scanning a list of processes and their snapshot information. The larger the process list, the longer it will take to GetSnapshotData()

A Simple Example

To illustrate this point, I put together a very rudimentary test to basically do the following:

- open a connection

- run

SELECT 1 - keep the connection open until the program ends

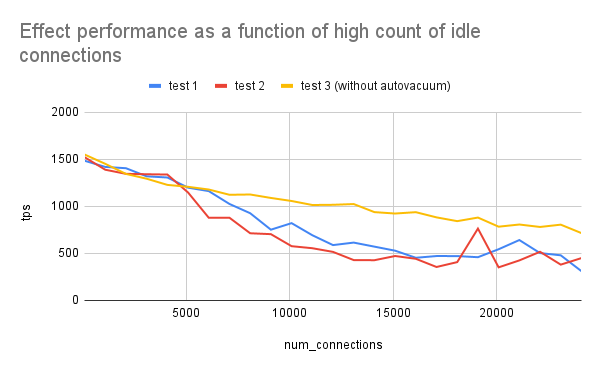

While running this simple program to keep thousands of idle connections open, I ran pgbench on the side and gathered the tps output (with flags --client=10 --transactions=5000`). The results of this test are below:

Granted, this was an older maching (128GB RAM on a 32-CPU VM with spindle disks on CentOS 7), but I think it still has the capability of illustrating the effect of increasing the number of idle connections. As we can see, when the number of idle connections increases, the throughput decreases. I ran two tests and their results are fairly similar. The spikes towards the end may have to do with caching or some other background activity. I purposely kept autovacuum = on for the two tests because a real system will likely have autovacuum on. For a third test, I turned off autovacuum, and while the performance was marginally better (because the active processes are no longer competing with autovacuum for I/O resources), we still see that scaling up idle connections will negatively affect performance.

How to Achieve High Throughput

If max_connections cannot be set to more than a few hundred, how do we achieve high throughput on a very busy enterprise-grade application? One of the simplest ways to address this is by using a connection pooler like pgbouncer, which will allow the thousands of application connections to share a relatively small pool of database sessions. One of the advantages of doing this is that because max_connections can be kept low, administrators can be more generous with work_mem, as each of the fewer processes can get a larger share of the memory pool. Other ways of addressing heavy client application traffic include leveraging a mix of replication with HAProxy to achieve read scaling.

Conclusion

We’ve briefly explored how connection scaling negatively affects database performance. Andres Freund has written a more comprehensive article on this very topic, and more analysis and insights can be found in his post. From both his tests and mine, it is very clear that when it comes to max_connections, the reality is often the case that less is more, and additional software and tools should be employed to achieve better throughput.