In my last blog post, I introduced the builder pattern in TypeScript and discussed how you can use it to get more accurate types in your code. It was all very abstract, so I thought it might be useful to show another more complex example. If you haven’t read my last blog, I’d recommend it, but I’m the kind of person to ignore that warning so no judgement here!

In this post, I show how the builder pattern can be used to create Reducers in a TypeScript React-Redux app. I discuss the benefits of that approach before walking through the code and explaining what it does at each step.

It’s not perfectly type-safe, but that’s not the goal. Instead, we use the builder pattern to create a type-safe boundary around unsafe code. That way, we can get the best of both worlds - a utility method that is both safe and maintainable.

Redux Reducers

I’ll assume you have used Redux before, but here’s a quick primer if not:

Redux is a state management library that’s usually used with React.

In Redux, there is a single global ‘store’ which contains the current state of the website.

The store is updated by dispatching an ‘action’ onto the store.

Each action has two properties, type and payload.

Attach a ‘reducer’ to the store to define how the state should change when an action is received.

Each reducer contains a number of cases, where each case handles a given type of action.

For a full explanation of those concepts and the terminology, read the official documentation.

Redux Type Safety

For the remainder of this post, we will be using Redux Toolkit, the official recommended way to develop Redux apps. However, you could easily tweak this code to work in a plain Redux project that doesn’t use Redux Toolkit.

In Redux Toolkit, you are expected to use ‘action creators’ rather than writing your actions as object literals. They are important later, so let’s start by writing a couple of action creators. I’ll assume our app is a counter, meaning the state is a number and we have two actions:

const incrementAction = createAction("increment");

const setAction = createAction<number, "set">("set");

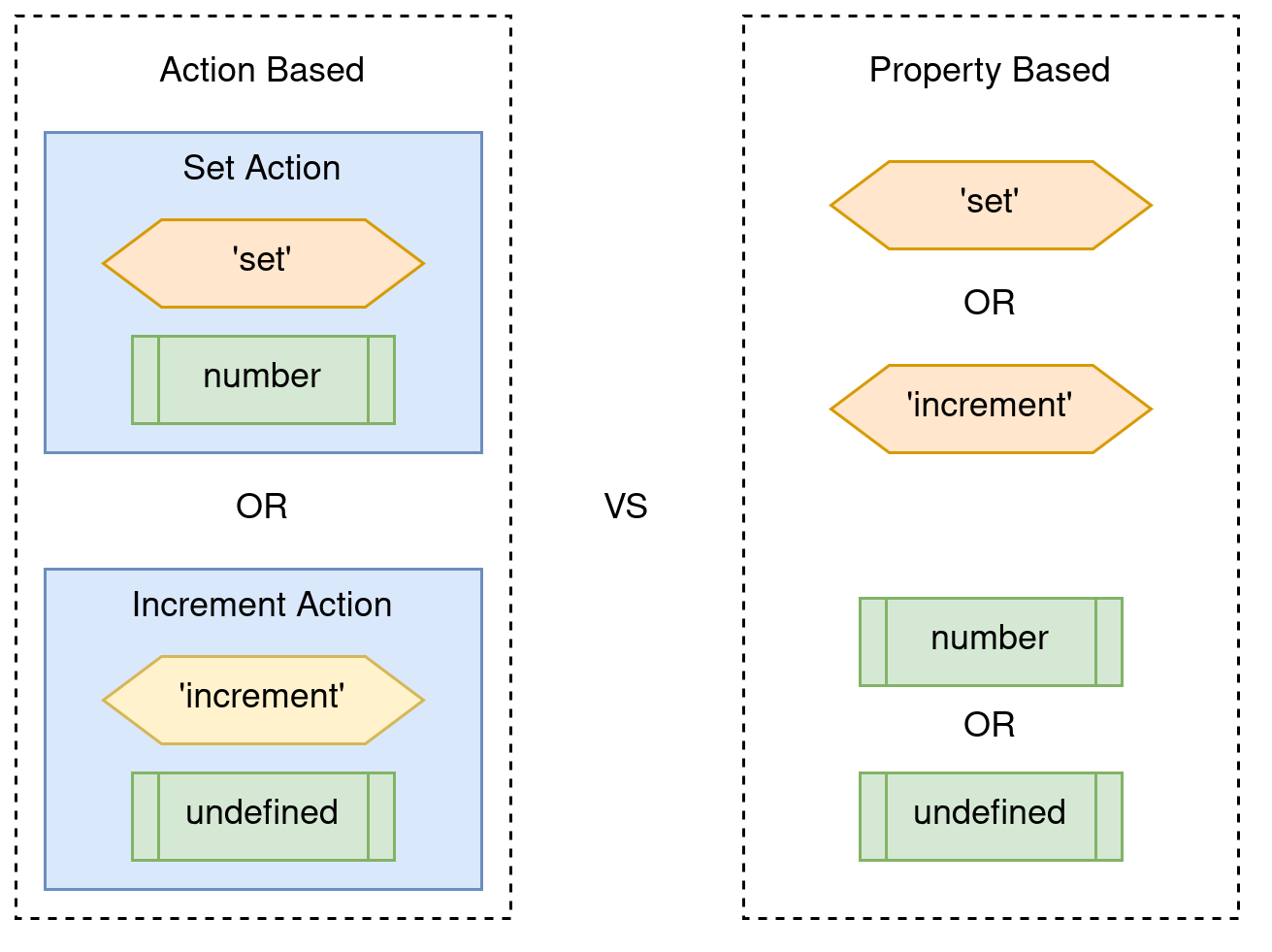

Now that we have our actions, there are two ways to create a reducer that handles them:

- From a map of action types to handlers

- Using a builder

Option 1: Using a Map

Here, you can call createReducer(), passing a map of action types to handlers, like this:

const reducer = createReducer(0, {

"increment": (state) => state + 1,

"set": (state, action: PayloadAction<number>) => action.payload

});

Then, we can dispatch actions onto the reducer. Note that this isn’t how you normally use a reducer, and it’s just to demonstrate the type safety.

const oldState = 0;

reducer(oldState, setAction(3));

reducer(oldState, incrementAction());

That’s all well and good, but there’s nothing stopping us dispatching an action that doesn’t exist on the reducer:

const decrementAction = createAction("decrement");

const oldState = 0;

reducer(oldState, decrementAction());

Likewise, there’s nothing saying we even need to pass the correct type of payload:

const oldState = 0;

reducer(oldState, {

type: "set",

payload: "this is meant to be a number"

});

Nothing we’ve seen so far has caused a compiler error.

Our decrement action would just do nothing, while passing the wrong payload type or would probably cause runtime errors.

It’s clear that this isn’t strongly typed at all.

Option 2: Using a Builder

First, note that this isn’t the builder that I promised in the intro. Redux Toolkit provides its own Reducer Builder which is insufficient for reasons that will soon become obvious.

const reducer = createReducer(0, (builder => builder

.addCase(incrementAction, (state) => state + 1)

.addCase(setAction, (state, action) => action.payload)

));

const oldState = 0;

reducer(oldState, setAction(3));

reducer(oldState, incrementAction());

As before, we can create our builder that handles the two actions, then dispatch actions to it. Also like before, we can dispatch a load of invalid actions without causing any compiler errors:

const decrementAction = createAction("decrement");

reducer(oldState, decrementAction());

reducer(oldState, {

type: "set",

payload: "this should be a number"

});

reducer(oldState, {

type: "nonexistent",

payload: "action"

});

That’s really not ideal, and essentially means that the core of your type-safe TS project is completely unsafe. There must be a better way, and there is:

Fixing it with Mutable Generic State

Let’s start with the end product, a type-safe Reducer Builder:

import { createReducer, PayloadAction, ActionCreatorWithPayload Reducer, Draft } from "@reduxjs/toolkit";

type ActionHandler<STATE, PAYLOAD> = (state: Draft<STATE>, payload: PAYLOAD) => STATE;

export class ReducerBuilder<STATE, ACTIONS extends PayloadAction<any, string>>{

private readonly initialState: STATE;

private readonly cases: Array<{type: string; handler: ActionHandler<STATE, any>}>;

private constructor(

initialState: STATE,

cases: Array<{type: string; handler: ActionHandler<STATE, any>}>

) {

this.initialState = initialState;

this.cases = cases;

}

static new<STATE>(initialState: STATE): ReducerBuilder<STATE, never> {

return new ReducerBuilder(initialState, [])

}

addCase<TYPE extends string, PAYLOAD>(

actionCreator: ActionCreatorWithPayload<PAYLOAD, TYPE>,

actionHandler: ActionHandler<STATE, PAYLOAD>

): ReducerBuilder<STATE, ACTIONS | PayloadAction<PAYLOAD, TYPE>> {

return new ReducerBuilder(

this.initialState,

[...this.cases, {type: actionCreator.type, handler: actionHandler}]

);

}

build(): ReduxReducer<STATE, ACTIONS> {

return createReducer(this.initialState, (builder => {

this.cases.forEach(({type, handler}) => {

builder.addCase(type,

(state: Draft<STATE>, action: PayloadAction<any, string>) =>

handler(state, action.payload)

);

})

}))

}

}

Before we dive into that code, let’s see what it can (and can’t) do:

const reducer = ReducerBuilder.new(0)

.addCase(incrementAction, (state) => state + 1)

.addCase(setAction, (state, payload) => payload)

.build();

const oldState = 0;

reducer(oldState, setAction(3));

reducer(oldState, incrementAction());

That’s not too impressive, since the syntax is pretty much the same as the Redux Toolkit builder. However, the main appeal of this builder is the type-safety. Both of these cause compile-time errors:

const oldState = 0;

reducer(oldState, {

type: "nonexistent",

payload: "action"

});

reducer(oldState, {

type: "set",

payload: "1"

});

Like the pipeline builder from the last post, the goal here was never end-to-end type safety. Instead, we guarantee that the builder is type-safe through its APIs. The implementation is unashamedly type-unsafe, and is only viable thanks to the restrictions on the methods.

We could go to the effort of improving the types inside the builder in multiple ways.

For example, we could use this.cases.forEach(<T extends string> in the build method to prevent losing type information.

We could also add another generic parameter to our class, tracking which action types map to each action payload, which would prevent the need to use any in the build method.

That’s not the point though. The power of the builder pattern comes from a type-safe boundary around unsafe code. By embracing that concept, we get the same level of confidence in our software with far less work, and avoid the maintainability issues that come from complex types.

Other useful bits

This reducer builder is useful, but it’s not enough on its own to get full type-safety in Redux. Your root reducer and root store will also need some help with their types, like this:

import {

combineReducers,

configureStore,

Dispatch,

getDefaultMiddleware

} from "@reduxjs/toolkit";

import { useDispatch } from "react-redux";

export type RootState = {

world: ReturnType<typeof worldReducer>;

player: ReturnType<typeof playerReducer>;

};

export type RootActions =

Parameters<typeof worldReducer>[1] |

Parameters<typeof playerReducer>[1];

export const rootReducer = combineReducers<RootState, RootActions>({

world: worldReducer,

player: playerReducer

});

export const rootStore = configureStore<RootState, RootActions, any>({

reducer: rootReducer,

middleware: [

...getDefaultMiddleware<RootState>()

] as const

});

export type AppDispatch = Dispatch<RootActions>;

export const useAppDispatch = () => useDispatch<AppDispatch>();

Then you can simply use Redux like normal inside your React components, but with full type-safety:

const Root: FunctionComponent = () => {

const dispatch = useAppDispatch();

const handleClick = () => {

return dispatch(playAction())

}

return <Button onClick={handleClick}>Start</Button>

}

If we haven’t configured handlers for playAction in either worldReducer or playerReducer, this won’t compile.

Perfect!

If you just want to take those snippets and use them, go for it!

It’s batteries-included and doesn’t have any real problems.

Often in my posts there’s a section at the end that says please don't actually use this - but not here!

Code Walkthrough

This section contains an in-depth walkthrough of the code snippet above. I skip over some of the background detail, so I’d recommend reading my last post first if you haven’t already.

To understand how this builder works, let’s think about what a reducer needs in terms of type information. When you call a reducer, it looks something like this:

const newState = reducer(oldState, action);

The newState and oldState variables are both the reducer’s state type, while the action parameter should be one of the actions that the reducer is configured to handle.

It’s fairly intuitive that our builder must have generic types for the state and the set of valid actions.

Of those two, the state type never changes but the set of valid actions must be mutable when we add cases to the reducer.

Each time we add a case, we should add a valid action type.

In this case, it’s not enough to just have a union of strings representing the valid action types.

If we did that, there would be no compile-time guarantee that the action’s payload is correct.

Instead, we need the generic type representing valid actions to be a union of PayloadAction.

This is the Redux Toolkit type representing an action with a given type and payload.

You specify the type and payload using generic parameters, like this:

type SetAction = PayloadAction<number, "set">;

Therefore, our class declaration looks like this:

export class ReducerBuilder<STATE, ACTIONS extends PayloadAction<any, string>>{

The state is configured via STATE, which can be any type, and the set of valid actions is configured via ACTIONS, which can be any payload action type.

In practice, this would actually be a union of many payload action types.

Also, note that the PayloadAction type can be configured to represent an action without a payload by passing undefined as its first generic parameter.

We could have used two generic parameters. One would be for the union of valid action types, and the other would be the union of valid action payloads.

However, that wouldn’t work properly. It would allow us to dispatch the action:

{

type: "increment",

payload: 5

}

This action has a type that is one of the valid options, and it has a payload that is also a valid option.

However, we specifically care about the combination of properties on the action.

A number payload is only valid on a set action, and any increment action with a payload is invalid.

Therefore, we have to use a union of PayloadAction objects.

Moving on to the actual class implementation, let’s look at the builder’s internal state:

private readonly initialState: STATE;

private readonly cases: Array<{type: string; handler: ActionHandler<STATE, any>}>;

At the top of the class, we define the two pieces of internal state.

The initialState property is simple, and is taken as a parameter when the builder is created, then used when creating the reducer.

The cases property is more complex, and maps action types to their handlers.

This uses the ActionHandler type defined at the top of the snippet:

type ActionHandler<STATE, PAYLOAD> = (state: Draft<STATE>, payload: PAYLOAD) => STATE;

This type simply represents a function that takes the current state and the payload from the received action, returning the new state.

The Draft type is part of Redux Toolkit, and allows us to directly mutate the state parameter without breaking things.

In Redux, you typically have to treat the state as immutable, so this just makes it a bit simpler to use.

Interestingly, our ACTIONS generic type doesn’t appear anywhere in the builder’s internal state.

It only exists at compile time to check that the reducer is valid.

There is never anything in our builder that actually fits that type.

Like before, we have a private constructor for internal use and a static factory method for external use:

private constructor(

initialState: STATE,

cases: Array<{type: string; handler: ActionHandler<STATE, any>}>

) {

this.initialState = initialState;

this.cases = cases;

}

static new<STATE>(initialState: STATE): ReducerBuilder<STATE, never> {

return new ReducerBuilder(initialState, [])

}

The static new method permanently sets the initial state of the reducer, and initialises the builder to have no cases.

That means that the second generic parameter, representing the union of all valid actions, is typed as never.

This type is unique because it never matches anything.

That makes sense - a reducer with no cases should accept no actions.

I have left the state and constructor separate to make it easier to explain, but you can combine the two as:

private constructor(

private readonly initialState: STATE,

private readonly cases: Array<{type: string; handler: ActionHandler<STATE, any>}>

) { }

To add a new case to the reducer, we invoke our mutator method, addCase:

addCase<TYPE extends string, PAYLOAD>(

actionCreator: ActionCreatorWithPayload<PAYLOAD, TYPE>,

actionHandler: ActionHandler<STATE, PAYLOAD>

): ReducerBuilder<STATE, ACTIONS | PayloadAction<PAYLOAD, TYPE>> {

return new ReducerBuilder(

this.initialState,

[...this.cases, {type: actionCreator.type, handler: actionHandler}]

);

}

When called, this method configures a handler for a given action type.

The actionCreator parameter specifies what action we are configuring a handler for.

It uses the Redux Toolkit ActionCreatorWithPayload type.

Like before, you can set the payload to undefined when representing an action with no payload.

The second parameter specifies what should happen to the state when the reducer receives that action. We create a new builder where the initial state stays the same but the cases map is extended. The new case is added to the end as an object containing the action type and action handler.

The ACTIONS generic parameter in the returned builder is explicitly specified as ACTIONS | PayloadAction<PAYLOAD, TYPE>.

This simply adds a new action into the ACTIONS union.

The new action is defined as having the type and payload from the action creator.

Finally, we look at the build method. This takes the builder’s current state and uses it to configure a Redux reducer:

build(): ReduxReducer<STATE, ACTIONS> {

return createReducer(this.initialState, (builder => {

this.cases.forEach(({type, handler}) => {

builder.addCase(type,

(state: Draft<STATE>, action: PayloadAction<any, string>) =>

handler(state, action.payload)

);

})

}))

}

There’s no fancy type magic going on here, just a call to the normal Redux Toolkit createReducer, using its builder mode.

For each case in the builder’s internal state, it adds a matching case to the reducer.

When it has added all cases, it is done and the reducer is ready to use.

Conclusion

Redux Reducers were the first time I realised the power of the builder pattern in TypeScript, and they’re still one of the best use-cases. They give you real type-safety, have basically no runtime cost, and are completely encapsulated which means there’s limited impact on maintainability. In my Redux projects, I went even further and added a similar builder for Redux Sagas, but I’m leaving that as an exercise to the reader.

I hope that this post gave you a better insight into how builders can be used to get better types in TypeScript. If not, at least you got some code snippets to copy-paste!

Feel free to contact me on Twitter with any questions, feedback, or to point out mistakes! I’d love to hear from you if you’ve found this useful and tried using builders in your own project. How did it go?