One of the tropes of detective movies is the almost miraculous ability to reconstruct an image from a blurry photograph. You just scan the picture, say “enhance!”, and voila, the face of the suspect or the registration number of their car appear on your computer screen.

With constant improvements in deep learning, we might eventually get there. In category theory, though, we do this all the time. We recover lost information. The procedure is based on the basic tenet of category theory: an object is defined by its interactions with the rest of the world. This is the basis of all universal constructions, the Yoneda lemma, Grothendieck fibration, Kan extensions, and practically everything else.

An iconic example is the construction of the left adjoint to a given functor, and that’s what we are going to study here. But first let me explain why I decided to pick this subject, and how it’s related to programming. I wanted to write a blog post about CPS (continuation passing style) and defunctionalization, and I stumbled upon an article in nLab that related defunctionalization to Freyd’s Adjoint Functor Theorem; in particular to the Solution Set Condition. Such an unexpected connection peaked my interest and I decided to dig deeper into it.

Adjunctions

Consider a functor from some category

to another category

.

A functor, in general, loses some data, so it’s normally impossible to invert it. It produces a “blurry” image of inside

. Its left adjoint is a functor from

to

that attempts to reconstruct lost information, to the best of its ability. Often the functor is forgetful, which means that it purposefully forgets some information. Its left adjoint is then called free, because it freely ad-libs the forgotten information.

Of course it’s not always possible, but under certain conditions such left adjoint exists. These conditions are spelled out in the Freyd’s General Adjoint Functor Theorem.

To understand them, we have to talk a little about size issues.

Size issues

A lot of interesting categories are large. It means that there are so many objects in the category that they don’t even form a set. The category of all sets, for instance, is large (there is no set of all sets). It’s also possible that morphisms between two objects don’t form a set.

A category in which objects form a set is called small, and a category in which hom-sets are sets is called locally small.

A lot of complexities in Freyd’s theorem are related to size issues, so it’s important to precisely spell out all the assumptions.

We assume that the source of the functor , the category

, is locally small. It must also be small-complete, that is, every small diagram in

must have a limit. (A small diagram is a functor from a small category.) We also want the functor

to be continuous, that is, to preserve all small limits.

If it weren’t for size issues, this would be enough to guarantee the existence of the left adjoint, and we’ll first sketch the proof for this simplified case. In the general case, there is one more condition, the Solution Set Condition, which we’ll discuss later.

Left adjoint and the comma category

Here’s the problem we are trying to solve. We have a functor that maps objects and morphisms from

to

. We want to define another functor

that goes in the opposite direction. We’re not looking for the inverse, so we’re not expecting the composition of this functor with

to be identity, but we want it to be related to identity by two natural transformations called unit and counit. Their components are, respectively:

and, as long as they satisfy some additional triangle identities, they will establish the adjunction .

We are going to define point-wise, so let’s pick an object

in

and try to propagate it back to

. To do that, we have to gather as much information about

as possible. We will propagate all this information back to

and find an object in

that “looks the same.” Think of this as creating a hologram of

and shipping it back to

.

All information about is encoded in morphisms so, in order to generate our hologram, we’ll gather all morphisms that originate in

. These morphisms form a category called the coslice category

.

The objects in are pairs

. In other words, these are all the arrows that emanate from

, indexed by their target objects

. But what really defines the structure of this category are morphisms between these arrows. A morphism in

from

to

is a morphism

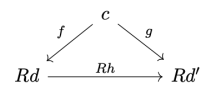

that makes the following triangle commute:

We now have complete information about encoded in the slice category, but we have no way to propagate it back to

. This is because, in general, the image of

doesn’t cover the whole of

. Even more importantly, not all morphisms in

have corresponding morphisms in

. We have to scale down our expectations, and define a partial hologram that does not capture all the information about

; only this part which can be back-propagated to

using the functor

. Such partial hologram is called a comma category

.

The objects of are pairs

, where

is an object in

. In other words, these are all the arrows emanating from

whose target is in the image of

. Again, the important structure is encoded in the morphisms of

. These are the arrows in

,

that make the following diagram commute in

Notice an interesting fact: we can interpret these triangles as commutation conditions in a cone whose apex is and whose base is formed by objects and morphisms in the image of

. But not all objects or morphism in the image of

are included. Only those morphisms that make the appropriate triangle commute–and these are exactly the morphisms that satisfy the cone condition. So the comma category builds a cone in

.

Constructing the limit

We can now take all this information about that’s been encoded in

and move it back to

. We define a projection functor

that maps

to

, thus forgetting the morphism

. What’s important, though, is that this functor keeps the information encoded in the morphisms of

, because these are morphisms in

.

The image of doesn’t necessarily cover the whole of

, because not every

has arrows coming from

. Similarly, only some morphisms, the ones that make the appropriate triangle in

commute, are picked by

. But those objects and morphisms that are in the image of

form a diagram in

. This diagram is our partial hologram, and we can use it to pick an object in

that looks almost exactly like

. That object is the limit of this diagram. We pick the limit of this diagram as the definition of

: the left adjoint of

acting on

.

Here’s the tricky part: we assumed that was small-complete, so every small diagram has a limit; but the diagram defined by

is not necessarily small. Let’s ignore this problem for a moment, and continue sketching the proof. We want to show that the mapping that assigns the limit of

to every

is left adjoint to

.

Let’s see if we can define the unit of the adjunction:

Since we have defined as the limit of the diagram

and

preserves limits (small limits, really; but we are ignoring size problems for the moment) then

must be the limit of the diagram

in

. But, as we noted before, the diagram

is exactly the base of the cone with the apex

that we used to define the comma category

. Since

is the limit of this diagram, there must be a unique morphism from any other cone to it. In particular there must be a morphism from

to it, because

is an apex of the cone defined by the comma category. And that’s the morphism we’ll chose as our

.

Incidentally, we can interpret itself as an object of the comma category

, namely the one defined by the pair

. In fact, this is the initial object in that category. If you pick any other object, say,

, you can always find a morphism

, which is just a leg, a projection, in the limiting cone that defines

. It is automatically a morphism in

because the following triangle commutes:

This is the triangle that defines as a morphism of cones, from the top cone with the apex

, to the bottom (limiting) cone with the apex

. We’ll use this interpretation later, when discussing the full version of the Freyd’s theorem.

We can also define the counit of the adjunction. Its component at is a morphism

First, we repeat our construction starting with . We define the comma category

and use

to create the diagram whose limit is

. We pick

to be a projection in the limiting cone. We are guaranteed that

is in the base of the cone, because it’s the image of

under

.

To complete this proof, one should show that the unit and counit are natural transformations and that they satisfy triangle identities.

End of a comma category

An interesting insight into this construction can be gained using the end calculus. In my previous post, I talked about (weighted) colimits as coends, but the same argument can be dualized to limits and ends. For instance, this is our comma category as a category of elements in the coend notation:

The limit of of the projection functor over the comma category can be written in the end notation as

This, in turn, can be rewritten as a weighted limit, with every weighted by the set

:

The pitchfork here is the power (cotensor) defined by the equation

You may think of as the product of

copies of the object

, where

is a set. The name power conveys the idea of iterated multiplication. Or, since power is a special case of exponentiation, you may think of

as a function object imitating mappings from

to

.

To continue, if the left adjoint exists, the weighted limit in question can be replaced by

which, using standard calculus of ends (see Appendix), can be shown to be isomorphic to . We end up with:

Solution set condition

So what about those pesky size issues? It’s one thing to demand the existence of all small limits, and a completely different thing to demand the existence of large limits (such requirement may narrow down the available categories to preorders). Since the comma category may be too large, maybe we can cut it down to size by carefully picking up a (small) set of objects out of all objects of . We may take some indexing set

and construct a family

of objects of

indexed by elements of

. It doesn’t have to be one family for all—we may pick a different family for every object

for which we are performing our construction.

Instead of using the whole comma category , we’ll limit ourselves to a set of arrows

. But in a comma category we also have morphisms between arrows. In fact they are the essential carriers of the structure of the comma category. Let’s have another look at these morphisms.

This commuting condition can be re-interpreted as a factorization of through

. It so happens that every morphism

can be trivially factorized through some

by picking

and

. But if we restrict the factors

to be members of the family

then not every

(for arbitrary

) can be automatically factorized. We have to demand it. That gives us the following:

Solution Set Condition: For every object there exists a small set

with an

-indexed family of objects

in

and a family of morphisms

, such that every morphism

can be factored through one of

. That is, there exists a morphism

such that

There is a shorthand for this statement: All comma categories admit weakly initial families of objects. We’ll come back to it later.

Freyd’s theorem

We can now formulate:

Freyd’s Adjoint Functor Theorem: If is a locally small and small-complete category, and the functor

is continuous (small-limit preserving), and it satisfies the solution set condition, then

has a left adjoint.

We’ve seen before that the key to defining the point-wise left adjoint was to find the initial object in the comma category . The problem is that this comma category may be large. So the trick is to split the proof into two parts: first defining a weakly initial object, and then constructing the actual initial object using equalizers. A weakly initial object has morphisms to every object in the category but, unlike its strong version, these morphisms don’t have to be unique.

An even weaker notion is that of a weakly initial set of objects. These are objects that among themselves have arrows to every object in the category, but it’s possible that no individual object has all the arrows. The solution set in Freyd’s theorem is such a weakly initial set in the comma category . Since we assumed that

is small-complete, we can take a product of these objects and show that it’s weakly initial. The proof then proceeds with the construction of the initial object.

The details of the proof can be found in any category theory text or in nLab.

Next we’ll see the application of these results to the problem of defunctionalization of computer programs.

Appendix

To show that

it’s enough to show that the hom-functors from an arbitrary object are isomorphic

I used the continuity of the hom-functor, the definition of the power (cotensor) and the ninja Yoneda lemma.

August 22, 2020 at 4:47 am

[…] Перевод статьи Бартоша Милевски «Freyd Adjoint Functor Theorem» (исходный текст расположен по адресу — Текст оригинальной статьи). […]

July 19, 2021 at 4:40 pm

Thank you. A very good reading