Considerations (review) of the ODROID H2, ODROID N2 and Raspberry Pi 4, in particular as home server

I’ve been a long time user of SBCs; as part of my equipment, I’ve always had the need for a small home server, which they fit increasingly well.

My previous SBC has been an ODROID XU4, which I’ve covered in a previous article.

I’ve been reasonably happy of it, however, my requirements overgrew its limitations, therefore, as soon as the second batch of ODROID H2 was available, I jumped at the chance to switch.

Like in the XU4 article, I will make some general considerations about small home servers and how to H2 fits the (my) requirements, and how ARM and x86 board nowadays relate.

Contents:

- Part 1: History and considerations

- Part 2: The ODROID H2

- Part 3: A comparison of H2, N2 and Pi 4

- Part 4: The future

- Conclusion

Part 1: History and considerations

What do I do with a home server?

My need for a home server started long ago, when a tenant of my apartment illegally downloaded a few songs, causing a fine of hundreds of Euros (I was the formal owner of the line). The simplest solution was to install a VPN service upstream.

At the time, the Raspberry Pi 2 fit the requirement good enough: although not powerful, it was cheap, small, and required very little power (with “very little”, I mean that I was able to power it via the USB of the modem router!).

VPN modem routers have been available for a long time, however, they were significantly underpowered: the RPi 2 itself could only handle around 10 MBits/s of traffic, and they were even slower. Plus, I wasn’t familiar with the supporting operating systems (like OpenWRT).

I think this shows the strength of SBCs: they’re cheap, flexible, and “powerful enough”.

With the time, I moved to a Raspberry Pi 3+, then an ODROID XU4. By the time I had the XU4, I started to consider the machine more than just a VPN router; it was time to start to have a home server in a substantial sense.

For example, it would have been very handy to have a Torrent client on it. And then, an SMB server, so that I could store on it all my music. And why not a filesharing service (Owncloud, at the time)?

The bumps

The XU4 was powerful enough, however, my first big bump was the availability of software.

The Torrent client I use, qBittorrent, had a significant bug. However, while on an x86 I would have just added the PPA and the machine would automatically be always up to date, with an ARM I couldn’t, because PPAs don’t often offer ARM builds. Therefore, I had to compile it.

And here I hit the second big bump: it was slow as molasses. Memory was also a limiting factor; I had 8 cores, but couldn’t use them all to compile qBittorent: each build thread took a significant amount of memory, exceeding the 2 GiB supplied.

All in all, I could have lived with this, however, I’ve also realized a fundamental problem of ARM boards: they all have an expiry date.

ARM boards come with an expiry date

The x86 design is standard. Within the limits of available power, one can still run the latest Linux version on x86(-64) machines from more than 15 years ago.

Now, a recent cause to rejoice was the upstreaming of the Linux support for Raspberry Pi boards.

However, this is misleading; the article recites “complete support for the Raspberry Pi 3B and the 3B+”, but this is not accurate: in order to have real complete support, one needs special distributions:

- there are special Ubuntu versions available for RPis from model 3 onwards,

- or Raspbian,

- or Armbian.

What will happen when the O/S maintainers will discontinue the support for a board? At some point, it’s bound to happen.

Answer: tough luck!

Why support for ARM boards is not fully mainlined?

Because ARM boards have wildly different architectures, and additionally, their design (and/or design of their components) is proprietary.

And bear in mind that with “wildly”, I mean that Raspberry Pis boot from the GPU; yes, their CPU is an addition to the GPU.

Note that we’re also talking about the most popular boards. The less popular will naturally have considerably more limited support and lifetime (and even potentially less stability, due to less dedicated manpower).

A specific example of the difference between a modified kernel and a vanilla one

Let’s take the XU4 as an example.

Clone the XU4 kernel repository:

git clone https://github.com/hardkernel/linux.git

add the vanilla kernel (upstream) repository:

cd linux

git remote add upstream git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/stable/linux-stable

git fetch upstream

and finally, compare the the (current) 4.14 kernel fork with the upstream base:

git cherry -v v4.14.165 4.14.165-172

+ ca0dd684c34471740feaff8bc3c79b8f2f4eec14 drm/exynos/mixer: abstract out output mode setup code

+ dbcb7e49bcb4e549344754ec3fa3541bf0d54c45 drm/exynos/mixer: move mode commit to enable callback

+ d02f1302043002c5fb9237452b01ab6734ffe968 drm/exynos/mixer: move resolution configuration to single function

[...]

+ d99d9fb971da13d02623b78d221766f7b8164349 ODROID-XU4: config: enable USB_IP

+ 87ac02b49f31e4a4eba706ec702180d84c918a7e Revert "regulator: s2mps11: Fix buck7 and buck8 wrong voltages"

+ ea79e60c4dc3b4121b4721704d3957bcc27867ad Update rtw_ap.c

Yikes! That’s 219 commits. Interestingly, some even revert commits of the mainstream kernel, for example:

git show bd6c354381692a9f99194881942bfd518e9da5e5

commit bd6c354381692a9f99194881942bfd518e9da5e5

Author: Mauro (mdrjr) Ribeiro <mauro.ribeiro@hardkernel.com>

Date: Wed Jun 20 09:43:37 2018 -0300

Revert "mmap: relax file size limit for regular files"

This reverts commit af760b568ef165ca90aec68aec112375481ab4cb.

diff --git a/mm/mmap.c b/mm/mmap.c

index f858b1f336af..f9c7747cd9e6 100644

--- a/mm/mmap.c

+++ b/mm/mmap.c

@@ -1318,7 +1318,7 @@ static inline int mlock_future_check(struct mm_struct *mm,

static inline u64 file_mmap_size_max(struct file *file, struct inode *inode)

{

if (S_ISREG(inode->i_mode))

- return MAX_LFS_FILESIZE;

+ return inode->i_sb->s_maxbytes;

if (S_ISBLK(inode->i_mode))

return MAX_LFS_FILESIZE;

Regardless of such changes being required, this is clearly not sustainable in the long term.

Amusingly, Hardkernel explicitly mentions that there are Tons of issues undocumented. :-x. However, don’t get me wrong - I appreciate their honesty.

Requirements

As with other subjects, there can be religious wars about home servers/ARM boards.

My personal approach is formulate the requirements as clearly as possible, then choose what fits, rather than first start with a set of popular boards to choose from.

In my case, I knew that the computer must:

- be as compatible with Linux as possible;

- have a relatively small power draw, with passively cooling being a big plus;

- have at least two SATA ports;

- be very powerful, for ARM standards.

On the other hand, price was not a requirement, within the limits of the cost of the machine being in the ballpark of 200$.

The last consideration is not trivial at all. If we consider an adult audience, with limited time, one needs to choose carefully how to invest time.

As a parent and professional software engineer, something I don’t like is to spend hours of my spare time chasing an obscure and undocumented setting, which will be fixed in a matter of months by somebody. I’d rather spend time studying, say, B+trees: this is a knowledge that is deep and permanent.

Of course, some people like to chase obscure settings for the sake of it, but for the rest, it’s sensible, in my opinion, to factor this aspect in the costs.

SATA ports were crucial for me (due to the mirroring). More in general though, SD media as only form of storage can be a serious concern. Some users are perfectly tolerant to the lack of responsiveness of the SD media; I’ve lived with it for long, but after experiencing the speed and responsiveness of the eMMC storage on the XU4, I’ll never go back to SD cards.

A factor that I didn’t consider, is ECC RAM. This is not trivial! Some users require it for any type of servers, even low-end, and this is important, because it eliminates entire classes of machines, H2 included.

The Raspeberry Pis have a large community of hobbysts, and a very wide amount of add-ons. Along with the small(er) form factor, they are definitely a better fit for hobby computing - but this was not my personal use case.

Ultimately, my takeaway of the H2 is that’s it’s a very interesting low-end home server - but in perspective, this is a specific set of requirements, so it’s not a board I’d suggest to everybody.

A brief look at the evolution of SBCs

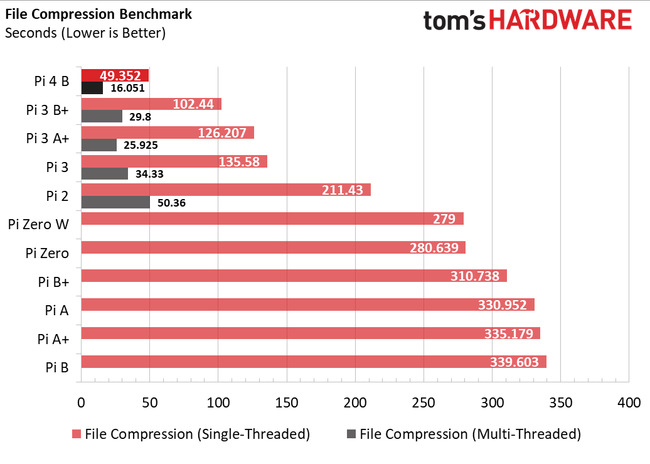

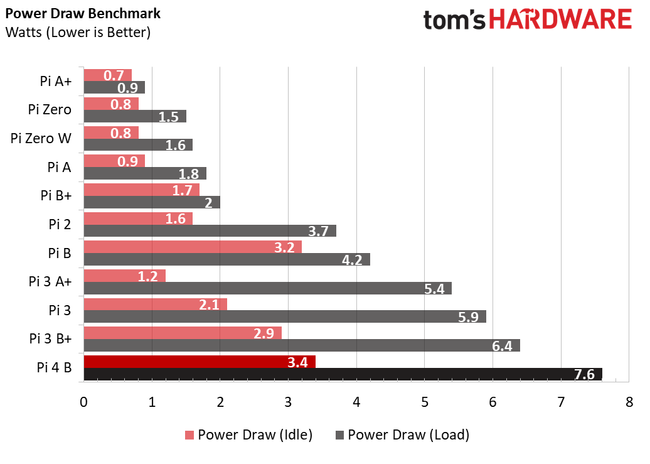

Raspberry Pis, and ARM boards in general, have increased their computing power considerably with each new release, but also their power consumption.

Tom’s hardware published a very thorough article about Raspberry Pis.

The most interesting diagrams are:

and:

There are a few considerations to make, however, the most important fact is that the RPi 4 draws around 3.5W in idle.

The consumption of the H2, is between 3W and 4W in idle, and 14 W under load (a bit less than twice as much as the RPi 4).

This is very interesting:

- in idle, they consume a comparable amount of power;

- under heavy load, the H2 consumes twice as much, but it’s also more than twice as powerful.

Something interesting is also the size of the RPi 4’s power supply:

As mentioned above, I used to power my Raspberry Pi 2 with the USB of my modem router!

Additionally, power supply is only side of the coin: the Raspberry 4 has been known for heating problems.

Yes, a long time has passed since the RPi 2 🙂

On the other hand, shifting the attention to the ODROID N2 gives a much more optimistic overview. Although the power adapter is even “brickier”,

the system consumes like an RPi 3, while being around twice as fast as an RPi 4.

Regardless, the natural conclusion is that SBCs are not very resource-light anymore. Users looking for the “old school” SBCs may opt for the Raspberry Pi Zero.

However, the RPi Zero is not a latest generation product; the Raspberry Pi foundation doesn’t really have a modern offer, aside the RPi 4.

Part 2: The ODROID H2

The bad: the enclosure

The idea behind the H2 enclosures is quite interesting: they offer four different models, targeting different configurations; for example, Type 2 is for those who want the minimal space occupation, while Type 3 is for those who, like me, want a system with two disks.

The cases are relatively expensive and very cheap quality. The reason for this is that since the H2 market is small, Hardkernel has virtually no competition when it comes to the enclosures; additionally, boards require an enclosure.

The Type 2, in Europe, costs around 12€; a cheap case for the Raspberry Pi 4, although smaller, costs around 1.5€.

The Type 3 is garbage, and I consider it a dishonest offer from the producers. It costs around 18€ in Europe, and besides the poor quality, it’s terribly designed.

The education video on YouTube is very misleading, to the point of being a lie.

See when the guy pushes the cables at 4’27”, again at 4’45” and again at 5’00”? That bends the SATA ports of the disks by 20/30°, which puts the disks at serious risk of breakage. The design is simply broken.

In order to avoid this, one has to leave the cables out of the enclosure like this:

which is certainly not as neat as expected.

Now, look at 5’07”, when he places the top cover. This is not how it works with real-wold units. Since these enclosures are cheaply produced, the internal white plastic columns don’t align with the top cover holes. Ironically, at that stage the case is closed, so one can’t align the columns with the fingers. The solution to this is screw the top cover just a little before the side walls, then force them in place.

Finally, something that I find very odd is why, considering that such enclosures are designed to be cheap, there are a handful of unneeded screws in the package.

I dread reopening the case again.

I certainly have experience on one only of the four available cases, but buyers beware!

Yet, there is an enclosure (which is not clear if it’s produced by Hardkernel or not), with a similar price, which hopefully is, like it seems, of better quality.

The OK

The machine is considerably bigger than an RPi - the board measures 11 x 11 x 4.3 cm. As a small home server, this shouldn’t be a problem, but generally speaking, the difference with the RPi boards can’t be ignored.

The good: all the rest

For the rest, the H2 is a great little machine:

- it runs very cool, even if it is passively cooled: in this moment, the CPU cores read 36/37°; so much for the 70°+ of the RPi 4!

- it has two Gigabit Ethernet ports: it supports out-of-the box (from a hardware perspective) router functionality;

- it has two SATA ports: allows a RAID1 (mirroring) configuration, which makes it a robust (of course, assuming one doesn’t require ECC RAM) file server;

- it has an M.2 (NVMe) port, that can be used, for example, for an NVMe disk;

- it also has an eMMC port, for those who don’t want solid-state drivers;

- a GPIO port is optionally available;

- it supports up to 32 GiB, in case somebody fancies memory-intensive tasks (I don’t).

I bought a fan, but it rarely spins. I think that unless the H2 is put under very heavy load or thermal pressure for long times, there’s no need to buy one.

The alternatives

The H2 is not the only mini PC available.

Gigabyte has a vast offer of mini PCs, called “BRIX”; the model with the same CPU costs around 200€, very similarly to the H2. The advantage is that it’s more polished, the disadvantage is that it’s not very customizable.

ASRock sells the interesting DeskMini barebone, but it’s in another price range, since it costs around 150€ without CPU/RAM/disk.

Intel has the so-called “NUC” series, but it’s considerably more expensive, even the comparable models.

All in all, in low-end x86 range, H2 has little competition; looking around, there are many (other) mini PC models available, but they are generally (if not always) fixed setups.

Part 3: A comparison of H2, N2 and Pi 4

The ODROID N2

Hardkernel seems to make higher-end SBCs, when compared to the Raspberry Foundation.

At the time of the Raspberry Pi 3, there was the XU4, and now, there is the N2.

However, while the XU4 had the same form factor of the RPi 3, the same doesn’t hold true for the N2: the size is around twice as much, 9 x 9 x 1.7 cm. The same considerations of the H2 apply - the size may be an important factor for some, but not for others.

The N2 supports eMMC, which is important for performance-seeking users (it makes only a minor difference in the overall price - see the pricing section).

The price strategy is the same as the XU4: compared to their RPi counterparts, higher performance is traded for higher price: a guideline price of 95€ for the N2 corresponds to 58€ of the RPi 4.

Support and community can be important requirements: while Hardkernel keeps supporting their products (at least, they are doing it for the XU4), it’s very likely that the N2 will have a shorter life; and there’s simply no comparison between the surrounding communities.

Benchmarks

The results of the excellent Phoronix Test Suite on the H2 and Pi 4, are publicly avaliable on openbenchmarking.org (the benchmark can also be run via phoronix-test-suite benchmark 1907127-HV-RASPBERRY81).

There isn’t any benchmark with all the three boards, however, a user uploaded the N2 results; the Pi 4 numbers match in both results, so a direct comparison can be established between the three.

Based on the tests of the suite - which are real-world applications - the H2 is consistently twice as powerful as the RPi 4, with peaks of 4x.

But the N2 is the big surprise: it essentially matches the H2 performance, while consuming 1/3rd of it under load; when compared to the RPis, it consumes roughly as an RPi 3; this is very impressive.

This is a snapshot of the openbenchmarking.org summary:

(the H2 performance can be considered the same as the N2)

Pricing

The pricing considerations require some clarifications:

- there is no single source of truth when it comes to pricing;

- special offers can’t be considered, as they change across time and models;

- it doesn’t make sense to compare the price of in-production models with out-of-production ones.

For the reasons above, I just chose a reference, large, seller (for almost everything), and based the totals on the prices of single components. The idea is not to consider the absolute prices, but the proportions between the models of the totals.

In Europe, right now, a basic H2 configuration costs:

- Board, Rev.B: 130€

- Power adapter, 15V/4A: 13€

- Case, Type 2: 12€

- RAM, 4 GiB PC4-19200: 20€

- eMMC, 16 GB: 20€

Total: 195€.

A comparable RPi 4 configuration costs:

- Board, Model B 4/2 GiB: 58/46€

- Power adapter, official: 9€

- Case, with fan and heatsinks: 12€

- Micro SD, 16 GB: 9€

Total: 88/76€

A comparable ODROID N2 configuration costs:

- Board: 95€

- Power adapter, 12V/2A: 12€

- Case: 7€

- Micro SD, 16 GB: 9€

Total: 123€

Something important to consider is that, for unclear reasons, in the Phoronix initial RPi 4 tests, the 4 GB model scored lower than the 2 GB one (by ~5%).

Additionally, the H2 performs marginally better with 2 RAM sticks, however, I didn’t consider the extra expense worth a (presumably) few percentage points increase in speed.

The prices above give a linear picture of the market; we could very roughly make the following associations:

- RPi 4 as low-end ARM SBC, for hobby computing,

- N2 as high-end ARM SBC, for lowest-end desktop/server purposes,

- H2 as (relatively) high-end x86 SBC, for low-end desktop/server purposes.

Note that I place the H2 in a different segment than N2, due to the consequences of being on an x86 platform. One could say that x86 [compatibility] has a price tag (and a power tag, too 😉).

Something worth reminding is that I’m skeptical about the RPi 4 quality from an engineering perspective:

- it has a flaw in the USB-C port,

- and it has heating problems.

Part 4: The future

ARM

It’s interesting to consider the short/mid term future of the ARM and Intel architectures, based on one hand on history, and on the other on announcements.

The Cortex A72 has been out for a while; it was introduced in 2016. The Raspberry Pi foundation introduced model 4 in 2019, relatively long after.

The ODROID N2 has also been released in 2019, while the underlying CPU, the Cortex A73, in 2017.

Therefore, generally speaking, we start to see the first SBCs roughly 2/3 years after the release of a new Cortex CPU.

A number of A7x evolutions has been introduced in the latest years (for simplification purposes, I’ll ignore the low-power A5x CPUs, even if they’re part of SBCs like the XU4 and N2):

Although one can’t take the marketing numbers seriously, new generations did actually introduce significant performance improvements, although I’m somewhat concerned about the power draw.

The nearest chip on the horizon that may land on SBCs is the Rockchip RK3588. Qualcomm produces already CPUs based on newer Cortex CPUs, however, they’re not targeted at SBCs.

x86

The Intel prospect doesn’t look too rosy.

While I’m a fan of the x86 SBCs, Intel clearly has only a modest interest in this segment - as a matter of fact, the H2 hasn’t been available for quite a long time after release, due to global shortage of the CPU it uses.

The H2 is based on the Celeron J4105, belonging to the Gemini Lake platform, and the Goldmont Plus architecture.

An updated platform has been very recently introduced by Intel, the Gemini Lake Refresh, that compared to the predecessor, has higher base frequency (1.5 vs. 2.0 GHz) and more GPU execution units (12 vs. 18).

On paper, this looks a good improvement, but in the mid/long term, it remains to be seen how much Intel will evolve compared to ARM, and if it will have enough interest.

The architecture succeeding the Goldmont Plus is called Tremont (WikiChip page and AnandTech article), and the first CPU has been announced (the Atom P5900).

Note that an architecture does not imply a family: for example, the Goldmont Plus architecture doesn’t include only the Atom family, but also the faster Celeron and Pentium Silver models; the H2’s CPU is indeed a Celeron.

The Tremont architecture is somewhat confusing though; from the Intel slides, it looks like Intel, at least for this architecture, is merging the Atom and Celeron models.

Without numbers at hand (rumors don’t count 😉), conclusions can’t be made. ARM has done great strides with the A7x family though, so it’s reasonable to have some doubts about the future performance of low-power Intel architectures.

Unfortunately, AMD doesn’t count much in this space - they have launched new embedded CPUs just today, but they belong to the old Ryzen generation. This is a pity, since the Ryzen 2 has been revolutionary, plus, very interestingly, the newly launched CPUs support ECC, which would make them rather unique SBCs (assuming a reasonable price).

Conclusion

As mentioned in the Pricing section, RPi 4, ODROID N2 and ODROID H2 lie on a continuum.

For my use case, the choice of the H2 is very obvious. If it wasn’t invented, I’d go for the N2, because of the Linux compatibility and performance (and the passive cooling). But there will be surely many other use cases, including those looking for a small price tag, where the RPi 4 fits very well.