Tutorial: Text Classification in Python Using spaCy

Text is an extremely rich source of information. Each minute, people send hundreds of millions of new emails and text messages. There's a veritable mountain of text data waiting to be mined for insights. But data scientists who want to glean meaning from all of that text data face a challenge: it is difficult to analyze and process because it exists in unstructured form.

In this tutorial, we'll take a look at how we can transform all of that unstructured text data into something more useful for analysis and natural language processing, using the helpful Python package spaCy (documentation).

Once we've done this, we'll be able to derive meaningful patterns and themes from text data. This is useful in a wide variety of data science applications: spam filtering, support tickets, social media analysis, contextual advertising, reviewing customer feedback, and more.

Specifically, we're going to take a high-level look at natural language processing (NLP). Then we'll work through some of the important basic operations for cleaning and analyzing text data with spaCy. Then we'll dive into text classification, specifically Logistic Regression Classification, using some real-world data (text reviews of Amazon's Alexa smart home speaker).

What is Natural Language Processing?

Natural language processing (NLP) is a branch of machine learning that deals with processing, analyzing, and sometimes generating human speech ("natural language").

There's no doubt that humans are still much better than machines at deterimining the meaning of a string of text. But in data science, we'll often encounter data sets that are far too large to be analyzed by a human in a reasonable amount of time. We may also encounter situations where no human is available to analyze and respond to a piece of text input. In these situations, we can use natural language processing techniques to help machines get some understanding of the text's meaning (and if necessary, respond accordingly).

For example, natural language processing is widely used in sentiment analysis, since analysts are often trying to determine the overall sentiment from huge volumes of text data that would be time-consuming for humans to comb through. It's also used in advertisement matching—determining the subject of a body of text and assigning a relevant advertisement automatically. And it's used in chatbots, voice assistants, and other applications where machines need to understand and quickly respond to input that comes in the form of natural human language.

Analyzing and Processing Text With spaCy

spaCy is an open-source natural language processing library for Python. It is designed particularly for production use, and it can help us to build applications that process massive volumes of text efficiently. First, let's take a look at some of the basic analytical tasks spaCy can handle.

Installing spaCy

We'll need to install spaCy and its English-language model before proceeding further. We can do this using the following command line commands:

pip install spacy

python -m spacy download en

We can also use spaCy in a Juypter Notebook. It's not one of the pre-installed libraries that Jupyter includes by default, though, so we'll need to run these commands from the notebook to get spaCy installed in the correct Anaconda directory. Note that we use ! in front of each command to let the Jupyter notebook know that it should be read as a command line command.

!pip install spacy

!python -m spacy download en

Tokenizing the Text

Tokenization is the process of breaking text into pieces, called tokens, and ignoring characters like punctuation marks (,. “ ‘) and spaces. spaCy's tokenizer takes input in form of unicode text and outputs a sequence of token objects.

Let's take a look at a simple example. Imagine we have the following text, and we'd like to tokenize it:

When learning data science, you shouldn't get discouraged.

Challenges and setbacks aren't failures, they're just part of the journey.

There are a couple of different ways we can appoach this. The first is called word tokenization, which means breaking up the text into individual words. This is a critical step for many language processing applications, as they often require input in the form of individual words rather than longer strings of text.

In the code below, we'll import spaCy and its English-language model, and tell it that we'll be doing our natural language processing using that model. Then we'll assign our text string to text. Using nlp(text), we'll process that text in spaCy and assign the result to a variable called my_doc.

At this point, our text has already been tokenized, but spaCy stores tokenized text as a doc, and we'd like to look at it in list form, so we'll create a for loop that iterates through our doc, adding each word token it finds in our text string to a list called token_list so that we can take a better look at how words are tokenized.

# Word tokenization

from spacy.lang.en import English

# Load English tokenizer, tagger, parser, NER and word vectors

nlp = English()

text = """When learning data science, you shouldn't get discouraged!

Challenges and setbacks aren't failures, they're just part of the journey. You've got this!"""

# "nlp" Object is used to create documents with linguistic annotations.

my_doc = nlp(text)

# Create list of word tokens

token_list = []

for token in my_doc:

token_list.append(token.text)

print(token_list)

['When', 'learning', 'data', 'science', ',', 'you', 'should', "n't", 'get', 'discouraged', '!', '\n', 'Challenges', 'and', 'setbacks', 'are', "n't", 'failures', ',', 'they', "'re", 'just', 'part', 'of', 'the', 'journey', '.', 'You', "'ve", 'got', 'this', '!']

As we can see, spaCy produces a list that contains each token as a separate item. Notice that it has recognized that contractions such as shouldn't actually represent two distinct words, and it has thus broken them down into two distinct tokens.

Fist we need to load language dictionaries, Here in abve example, we are loading english dictionary using English() class and creating nlp nlp object. "nlp" object is used to create documents with linguistic annotations and various nlp properties. After creating document, we are creating a token list.

If we want, we can also break the text into sentences rather than words. This is called sentence tokenization. When performing sentence tokenization, the tokenizer looks for specific characters that fall between sentences, like periods, exclaimation points, and newline characters. For sentence tokenization, we will use a preprocessing pipeline because sentence preprocessing using spaCy includes a tokenizer, a tagger, a parser and an entity recognizer that we need to access to correctly identify what's a sentence and what isn't.

In the code below,spaCy tokenizes the text and creates a Doc object. This Doc object uses our preprocessing pipeline's components tagger,parser and entity recognizer to break the text down into components. From this pipeline we can extract any component, but here we're going to access sentence tokens using the sentencizer component.

# sentence tokenization

# Load English tokenizer, tagger, parser, NER and word vectors

nlp = English()

# Create the pipeline 'sentencizer' component

sbd = nlp.create_pipe('sentencizer')

# Add the component to the pipeline

nlp.add_pipe(sbd)

text = """When learning data science, you shouldn't get discouraged!

Challenges and setbacks aren't failures, they're just part of the journey. You've got this!"""

# "nlp" Object is used to create documents with linguistic annotations.

doc = nlp(text)

# create list of sentence tokens

sents_list = []

for sent in doc.sents:

sents_list.append(sent.text)

print(sents_list)

["When learning data science, you shouldn't get discouraged!", "\nChallenges and setbacks aren't failures, they're just part of the journey.", "You've got this!"]

Again, spaCy has correctly parsed the text into the format we want, this time outputting a list of sentences found in our source text.

Cleaning Text Data: Removing Stopwords

Most text data that we work with is going to contain a lot of words that aren't actually useful to us. These words, called stopwords, are useful in human speech, but they don't have much to contribute to data analysis. Removing stopwords helps us eliminate noise and distraction from our text data, and also speeds up the time analysis takes (since there are fewer words to process).

Let's take a look at the stopwords spaCy includes by default. We'll import spaCy and assign the stopwords in its English-language model to a variable called spacy_stopwords so that we can take a look.

#Stop words

#importing stop words from English language.

import spacy

spacy_stopwords = spacy.lang.en.stop_words.STOP_WORDS

#Printing the total number of stop words:

print('Number of stop words:

#Printing first ten stop words:

print('First ten stop words:

Number of stop words: 312

First ten stop words: ['was', 'various', 'fifty', "'s", 'used', 'once', 'because', 'himself', 'can', 'name', 'many', 'seems', 'others', 'something', 'anyhow', 'nowhere', 'serious', 'forty', 'he', 'now']

As we can see, spaCy's default list of stopwords includes 312 total entries, and each entry is a single word. We can also see why many of these words wouldn't be useful for data analysis. Transition words like nevertheless, for example, aren't necessary for understanding the basic meaning of a sentence. And other words like somebody are too vague to be of much use for NLP tasks.

If we wanted to, we could also create our own customized list of stopwords. But for our purposes in this tutorial, the default list that spaCy provides will be fine.

Removing Stopwords from Our Data

Now that we've got our list of stopwords, let's use it to remove the stopwords from the text string we were working on in the previous section. Our text is already stored in the variable text, so we don't need to define that again.

Instead, we'll create an empty list called filtered_sent and then iterate through our doc variable to look at each tokenized word from our source text. spaCy includes a bunch of helpful token attributes, and we'll use one of them called is_stop to identify words that aren't in the stopword list and then append them to our filtered_sent list.

from spacy.lang.en.stop_words import STOP_WORDS

#Implementation of stop words:

filtered_sent=[]

# "nlp" Object is used to create documents with linguistic annotations.

doc = nlp(text)

# filtering stop words

for word in doc:

if word.is_stop==False:

filtered_sent.append(word)

print("Filtered Sentence:",filtered_sent)

Filtered Sentence: [learning, data, science, ,, discouraged, !,

, Challenges, setbacks, failures, ,, journey, ., got, !]

It's not too difficult to see why stopwords can be helpful. Removing them has boiled our original text down to just a few words that give us a good idea of what the sentences are discussing: learning data science, and discouraging challenges and setbacks along that journey.

Lexicon Normalization

Lexicon normalization is another step in the text data cleaning process. In the big picture, normalization converts high dimensional features into low dimensional features which are appropriate for any machine learning model. For our purposes here, we're only going to look at lemmatization, a way of processing words that reduces them to their roots.

Lemmatization

Lemmatization is a way of dealing with the fact that while words like connect, connection, connecting, connected, etc. aren't exactly the same, they all have the same essential meaning: connect. The differences in spelling have grammatical functions in spoken language, but for machine processing, those differences can be confusing, so we need a way to change all the words that are forms of the word connect into the word connect itself.

One method for doing this is called stemming. Stemming involves simply lopping off easily-identified prefixes and suffixes to produce what's often the simplest version of a word. Connection, for example, would have the -ion suffix removed and be correctly reduced to connect. This kind of simple stemming is often all that's needed, but lemmatization—which actually looks at words and their roots (called lemma) as described in the dictionary—is more precise (as long as the words exist in the dictionary).

Since spaCy includes a build-in way to break a word down into its lemma, we can simply use that for lemmatization. In the following very simple example, we'll use .lemma_ to produce the lemma for each word we're analyzing.

# Implementing lemmatization

lem = nlp("run runs running runner")

# finding lemma for each word

for word in lem:

print(word.text,word.lemma_)

run run

runs run

running run

runner runner

Part of Speech (POS) Tagging

A word's part of speech defines its function within a sentence. A noun, for example, identifies an object. An adjective describes an object. A verb describes action. Identifying and tagging each word's part of speech in the context of a sentence is called Part-of-Speech Tagging, or POS Tagging.

Let's try some POS tagging with spaCy! We'll need to import its en_core_web_sm model, because that contains the dictionary and grammatical information required to do this analysis. Then all we need to do is load this model with .load() and loop through our new docs variable, identifying the part of speech for each word using .pos_.

(Note the u in u"All is well that ends well." signifies that the string is a Unicode string.)

# POS tagging

# importing the model en_core_web_sm of English for vocabluary, syntax & entities

import en_core_web_sm

# load en_core_web_sm of English for vocabluary, syntax & entities

nlp = en_core_web_sm.load()

# "nlp" Objectis used to create documents with linguistic annotations.

docs = nlp(u"All is well that ends well.")

for word in docs:

print(word.text,word.pos_)

All DET

is VERB

well ADV

that DET

ends VERB

well ADV

. PUNCT

Hooray! spaCy has correctly identified the part of speech for each word in this sentence. Being able to identify parts of speech is useful in a variety of NLP-related contexts, because it helps more accurately understand input sentences and more accurately construct output responses.

Entity Detection

Entity detection, also called entity recognition, is a more advanced form of language processing that identifies important elements like places, people, organizations, and languages within an input string of text. This is really helpful for quickly extracting information from text, since you can quickly pick out important topics or indentify key sections of text.

Let's try out some entity detection using a few paragraphs from this recent article in the Washington Post. We'll use .label to grab a label for each entity that's detected in the text, and then we'll take a look at these entities in a more visual format using spaCy's displaCy visualizer.

#for visualization of Entity detection importing displacy from spacy:

from spacy import displacy

nytimes= nlp(u"""New York City on Tuesday declared a public health emergency and ordered mandatory measles vaccinations amid an outbreak, becoming the latest national flash point over refusals to inoculate against dangerous diseases.

At least 285 people have contracted measles in the city since September, mostly in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood. The order covers four Zip codes there, Mayor Bill de Blasio (D) said Tuesday.

The mandate orders all unvaccinated people in the area, including a concentration of Orthodox Jews, to receive inoculations, including for children as young as 6 months old. Anyone who resists could be fined up to $1,000.""")

entities=[(i, i.label_, i.label) for i in nytimes.ents]

entities

[(New York City, 'GPE', 384),

(Tuesday, 'DATE', 391),

(At least 285, 'CARDINAL', 397),

(September, 'DATE', 391),

(Brooklyn, 'GPE', 384),

(Williamsburg, 'GPE', 384),

(four, 'CARDINAL', 397),

(Bill de Blasio, 'PERSON', 380),

(Tuesday, 'DATE', 391),

(Orthodox Jews, 'NORP', 381),

(6 months old, 'DATE', 391),

(up to $1,000, 'MONEY', 394)]

Using this technique, we can identify a variety of entities within the text. The spaCy documentation provides a full list of supported entity types, and we can see from the short example above that it's able to identify a variety of different entity types, including specific locations (GPE), date-related words (DATE), important numbers (CARDINAL), specific individuals (PERSON), etc.

Using displaCy we can also visualize our input text, with each identified entity highlighted by color and labeled. We'll use style = "ent" to tell displaCy that we want to visualize entities here.

displacy.render(nytimes, style = "ent",jupyter = True)

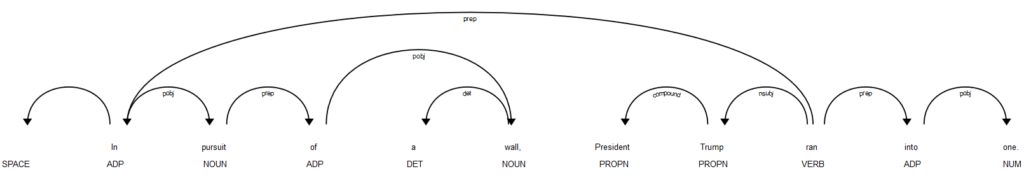

Dependency Parsing

Depenency parsing is a language processing technique that allows us to better determine the meaning of a sentence by analyzing how it's constructed to determine how the individual words relate to each other.

Consider, for example, the sentence "Bill throws the ball." We have two nouns (Bill and ball) and one verb (throws). But we can't just look at these words individually, or we may end up thinking that the ball is throwing Bill! To understand the sentence correctly, we need to look at the word order and sentence structure, not just the words and their parts of speech.

Doing this is quite complicated, but thankfully spaCy will take care of the work for us! Below, let's give spaCy another short sentence pulled from the news headlines. Then we'll use another spaCy called noun_chunks, which breaks the input down into nouns and the words describing them, and iterate through each chunk in our source text, identifying the word, its root, its dependency identification, and which chunk it belongs to.

docp = nlp (" In pursuit of a wall, President Trump ran into one.")

for chunk in docp.noun_chunks:

print(chunk.text, chunk.root.text, chunk.root.dep_,

chunk.root.head.text)

pursuit pursuit pobj In

a wall wall pobj of

President Trump Trump nsubj ran

This output can be a little bit difficult to follow, but since we've already imported the displaCy visualizer, we can use that to view a dependency diagraram using style = "dep" that's much easier to understand:

displacy.render(docp, style="dep", jupyter= True)

Of course, we can also check out spaCy's documentation on dependency parsing to get a better understanding of the different labels that might get applied to our text depending on how each sentence is intrepreted.

Word Vector Representation

When we're looking at words alone, it's difficult for a machine to understand connections that a human would understand immediately. Engine and car, for example, have what might seem like an obvious connection (cars run using engines), but that link is not so obvious to a computer.

Thankfully, there's a way we can represent words that captures more of these sorts of connections. A word vector is a numeric representation of a word that commuicates its relationship to other words.

Each word is interpreted as a unique and lenghty array of numbers. You can think of these numbers as being something like GPS coordinates. GPS coordinates consist of two numbers (latitude and longitude), and if we saw two sets GPS coordinates that were numberically close to each other (like 43,-70, and 44,-70), we would know that those two locations were relatively close together. Word vectors work similarly, although there are a lot more than two coordinates assigned to each word, so they're much harder for a human to eyeball.

Using spaCy's en_core_web_sm model, let's take a look at the length of a vector for a single word, and what that vector looks like using .vector and .shape.

import en_core_web_sm

nlp = en_core_web_sm.load()

mango = nlp(u'mango')

print(mango.vector.shape)

print(mango.vector)

(96,)

[ 1.0466383 -1.5323697 -0.72177905 -2.4700649 -0.2715162 1.1589639

1.7113379 -0.31615403 -2.0978343 1.837553 1.4681302 2.728043

-2.3457408 -5.17184 -4.6110015 -0.21236466 -0.3029521 4.220028

-0.6813917 2.4016762 -1.9546705 -0.85086954 1.2456163 1.5107994

0.4684736 3.1612053 0.15542296 2.0598564 3.780035 4.6110964

0.6375268 -1.078107 -0.96647096 -1.3939928 -0.56914186 0.51434743

2.3150034 -0.93199825 -2.7970662 -0.8540115 -3.4250052 4.2857723

2.5058174 -2.2150877 0.7860181 3.496335 -0.62606215 -2.0213525

-4.47421 1.6821622 -6.0789204 0.22800982 -0.36950028 -4.5340714

-1.7978683 -2.080299 4.125556 3.1852438 -3.286446 1.0892276

1.017115 1.2736416 -0.10613725 3.5102775 1.1902348 0.05483437

-0.06298041 0.8280688 0.05514218 0.94817173 -0.49377063 1.1512338

-0.81374085 -1.6104267 1.8233354 -2.278403 -2.1321895 0.3029334

-1.4510616 -1.0584296 -3.5698352 -0.13046083 -0.2668339 1.7826645

0.4639858 -0.8389523 -0.02689964 2.316218 5.8155413 -0.45935947

4.368636 1.6603007 -3.1823301 -1.4959551 -0.5229269 1.3637555 ]

There's no way that a human could look at that array and identify it as meaning "mango," but representing the word this way works well for machines, because it allows us to represent both the word's meaning and its "proximity" to other similar words using the coordinates in the array.

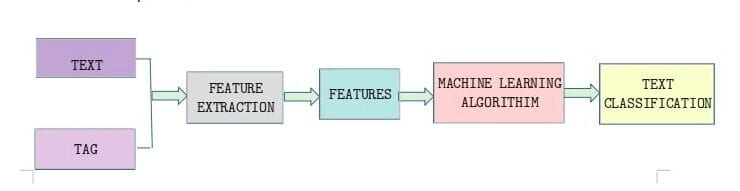

Text Classification

Now that we've looked at some of the cool things spaCy can do in general, let's look at at a bigger real-world application of some of these natural language processing techniques: text classification. Quite often, we may find ourselves with a set of text data that we'd like to classify according to some parameters (perhaps the subject of each snippet, for example) and text classification is what will help us to do this.

The diagram below illustrates the big-picture view of what we want to do when classifying text. First, we extract the features we want from our source text (and any tags or metadata it came with), and then we feed our cleaned data into a machine learning algorithm that do the classification for us.

Importing Libraries

We'll start by importing the libraries we'll need for this task. We've already imported spaCy, but we'll also want pandas and scikit-learn to help with our analysis.

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer,TfidfVectorizer

from sklearn.base import TransformerMixin

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

Loading Data

Above, we have looked at some simple examples of text analysis with spaCy, but now we'll be working on some Logistic Regression Classification using scikit-learn. To make this more realistic, we're going to use a real-world data set—this set of Amazon Alexa product reviews.

This data set comes as a tab-separated file (.tsv). It has has five columns: rating, date, variation, verified_reviews, feedback.

rating denotes the rating each user gave the Alexa (out of 5). date indicates the date of the review, and variation describes which model the user reviewed. verified_reviews contains the text of each review, and feedback contains a sentiment label, with 1 denoting positive sentiment (the user liked it) and 0 denoting negative sentiment (the user didn't).

This dataset has consumer reviews of amazon Alexa products like Echos, Echo Dots, Alexa Firesticks etc. What we're going to do is develop a classification model that looks at the review text and predicts whether a review is positive or negative. Since this data set already includes whether a review is positive or negative in the feedback column, we can use those answers to train and test our model. Our goal here is to produce an accurate model that we could then use to process new user reviews and quickly determine whether they were positive or negative.

Let's start by reading the data into a pandas dataframe and then using the built-in functions of pandas to help us take a closer look at our data.

# Loading TSV file

df_amazon = pd.read_csv ("datasets/amazon_alexa.tsv", sep="\t")

# Top 5 records

df_amazon.head()

| rating | date | variation | verified_reviews | feedback | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 31-Jul-18 | Charcoal Fabric | Love my Echo! | 1 |

| 1 | 5 | 31-Jul-18 | Charcoal Fabric | Loved it! | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 31-Jul-18 | Walnut Finish | Sometimes while playing a game, you can answer... | 1 |

| 3 | 5 | 31-Jul-18 | Charcoal Fabric | I have had a lot of fun with this thing. My 4 ... | 1 |

| 4 | 5 | 31-Jul-18 | Charcoal Fabric | Music | 1 |

# shape of dataframe

df_amazon.shape

(3150, 5)

# View data information

df_amazon.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 3150 entries, 0 to 3149

Data columns (total 5 columns):

rating 3150 non-null int64

date 3150 non-null object

variation 3150 non-null object

verified_reviews 3150 non-null object

feedback 3150 non-null int64

dtypes: int64(2), object(3)

memory usage: 123.1+ KB

# Feedback Value count

df_amazon.feedback.value_counts()

1 2893

0 257

Name: feedback, dtype: int64

Tokening the Data With spaCy

Now that we know what we're working with, let's create a custom tokenizer function using spaCy. We'll use this function to automatically strip information we don't need, like stopwords and punctuation, from each review.

We'll start by importing the English models we need from spaCy, as well as Python's string module, which contains a helpful list of all punctuation marks that we can use in string.punctuation. We'll create variables that contain the punctuation marks and stopwords we want to remove, and a parser that runs input through spaCy's English module.

Then, we'll create a spacy_tokenizer() function that accepts a sentence as input and processes the sentence into tokens, performing lemmatization, lowercasing, and removing stop words. This is similar to what we did in the examples earlier in this tutorial, but now we're putting it all together into a single function for preprocessing each user review we're analyzing.

import string

from spacy.lang.en.stop_words import STOP_WORDS

from spacy.lang.en import English

# Create our list of punctuation marks

punctuations = string.punctuation

# Create our list of stopwords

nlp = spacy.load('en')

stop_words = spacy.lang.en.stop_words.STOP_WORDS

# Load English tokenizer, tagger, parser, NER and word vectors

parser = English()

# Creating our tokenizer function

def spacy_tokenizer(sentence):

# Creating our token object, which is used to create documents with linguistic annotations.

mytokens = parser(sentence)

# Lemmatizing each token and converting each token into lowercase

mytokens = [ word.lemma_.lower().strip() if word.lemma_ != "-PRON-" else word.lower_ for word in mytokens ]

# Removing stop words

mytokens = [ word for word in mytokens if word not in stop_words and word not in punctuations ]

# return preprocessed list of tokens

return mytokens

Defining a Custom Transformer

To further clean our text data, we'll also want to create a custom transformer for removing initial and end spaces and converting text into lower case. Here, we will create a custom predictors class wich inherits the TransformerMixin class. This class overrides the transform, fit and get_parrams methods. We'll also create a clean_text() function that removes spaces and converts text into lowercase.

# Custom transformer using spaCy

class predictors(TransformerMixin):

def transform(self, X, **transform_params):

# Cleaning Text

return [clean_text(text) for text in X]

def fit(self, X, y=None, **fit_params):

return self

def get_params(self, deep=True):

return {}

# Basic function to clean the text

def clean_text(text):

# Removing spaces and converting text into lowercase

return text.strip().lower()

Vectorization Feature Engineering (TF-IDF)

When we classify text, we end up with text snippets matched with their respective labels. But we can't simply use text strings in our machine learning model; we need a way to convert our text into something that can be represented numerically just like the labels (1 for positive and 0 for negative) are. Classifying text in positive and negative labels is called sentiment analysis. So we need a way to represent our text numerically.

One tool we can use for doing this is called Bag of Words. BoW converts text into the matrix of occurrence of words within a given document. It focuses on whether given words occurred or not in the document, and it generates a matrix that we might see referred to as a BoW matrix or a document term matrix.

We can generate a BoW matrix for our text data by using scikit-learn's CountVectorizer. In the code below, we're telling CountVectorizer to use the custom spacy_tokenizer function we built as its tokenizer, and defining the ngram range we want.

N-grams are combinations of adjacent words in a given text, where n is the number of words that incuded in the tokens. for example, in the sentence "Who will win the football world cup in 2022?" unigrams would be a sequence of single words such as "who", "will", "win" and so on. Bigrams would be a sequence of 2 contiguous words such as "who will", "will win", and so on. So the ngram_range parameter we'll use in the code below sets the lower and upper bounds of the our ngrams (we'll be using unigrams). Then we'll assign the ngrams to bow_vector.

bow_vector = CountVectorizer(tokenizer = spacy_tokenizer, ngram_range=(1,1))

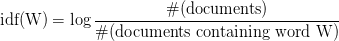

We'll also want to look at the TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) for our terms. This sounds complicated, but it's simply a way of normalizing our Bag of Words(BoW) by looking at each word's frequency in comparison to the document frequency. In other words, it's a way of representing how important a particular term is in the context of a given document, based on how many times the term appears and how many other documents that same term appears in. The higher the TF-IDF, the more important that term is to that document.

We can represent this with the following mathematical equation:

Of course, we don't have to calculate that by hand! We can generate TF-IDF automatically using scikit-learn's TfidfVectorizer. Again, we'll tell it to use the custom tokenizer that we built with spaCy, and then we'll assign the result to the variable tfidf_vector.

tfidf_vector = TfidfVectorizer(tokenizer = spacy_tokenizer)

Splitting The Data into Training and Test Sets

We're trying to build a classification model, but we need a way to know how it's actually performing. Dividing the dataset into a training set and a test set the tried-and-true method for doing this. We'll use half of our data set as our training set, which will include the correct answers. Then we'll test our model using the other half of the data set without giving it the answers, to see how accurately it performs.

Conveniently, scikit-learn gives us a built-in function for doing this: train_test_split(). We just need to tell it the feature set we want it to split (X), the labels we want it to test against (ylabels), and the size we want to use for the test set (represented as a percentage in decimal form).

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X = df_amazon['verified_reviews'] # the features we want to analyze

ylabels = df_amazon['feedback'] # the labels, or answers, we want to test against

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, ylabels, test_size=0.3)

Creating a Pipeline and Generating the Model

Now that we're all set up, it's time to actually build our model! We'll start by importing the LogisticRegression module and creating a LogisticRegression classifier object.

Then, we'll create a pipeline with three components: a cleaner, a vectorizer, and a classifier. The cleaner uses our predictors class object to clean and preprocess the text. The vectorizer uses countvector objects to create the bag of words matrix for our text. The classifier is an object that performs the logistic regression to classify the sentiments.

Once this pipeline is built, we'll fit the pipeline components using fit().

# Logistic Regression Classifier

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

classifier = LogisticRegression()

# Create pipeline using Bag of Words

pipe = Pipeline([("cleaner", predictors()),

('vectorizer', bow_vector),

('classifier', classifier)])

# model generation

pipe.fit(X_train,y_train)

Pipeline(memory=None,

steps=[('cleaner', <__main__.predictors object at 0x00000254DA6F8940>), ('vectorizer', CountVectorizer(analyzer='word', binary=False, decode_error='strict',

dtype=<class 'numpy.int64'>, encoding='utf-8', input='content',

lowercase=True, max_df=1.0, max_features=None, min_df=1,

...ty='l2', random_state=None, solver='liblinear', tol=0.0001,

verbose=0, warm_start=False))])

Evaluating the Model

Let's take a look at how our model actually performs! We can do this using the metrics module from scikit-learn. Now that we've trained our model, we'll put our test data through the pipeline to come up with predictions. Then we'll use various functions of the metrics module to look at our model's accuracy, precision, and recall.

- Accuracy refers to the percentage of the total predictions our model makes that are completely correct.

- Precision describes the ratio of true positives to true positives plus false positives in our predictions.

- Recall describes the ratio of true positives to true positives plus false negatives in our predictions.

The documentation links above offer more details and more precise definitions of each term, but the bottom line is that all three metrics are measured from 0 to 1, where 1 is predicting everything completely correctly. Therefore, the closer our model's scores are to 1, the better.

from sklearn import metrics

# Predicting with a test dataset

predicted = pipe.predict(X_test)

# Model Accuracy

print("Logistic Regression Accuracy:",metrics.accuracy_score(y_test, predicted))

print("Logistic Regression Precision:",metrics.precision_score(y_test, predicted))

print("Logistic Regression Recall:",metrics.recall_score(y_test, predicted))

Logistic Regression Accuracy: 0.9417989417989417

Logistic Regression Precision: 0.9528508771929824

Logistic Regression Recall: 0.9863791146424518

In other words, overall, our model correctly identified a comment's sentiment 94.1% of the time. When it predicted a review was positive, that review was actually positive 95% of the time. When handed a positive review, our model identified it as positive 98.6% of the time

Resources and Next Steps

Over the course of this tutorial, we've gone from performing some very simple text analysis operations with spaCy to building our own machine learning model with scikit-learn. Of course, this is just the beginning, and there's a lot more that both spaCy and scikit-learn have to offer Python data scientists.

Here are some links to a few helpful resources:

- Scikit-learn documentation

- spaCy documentation

- Dataquest's Machine Learning Course on Linear Regression in Python; many other machine learning courses are also available in our Data Scientist path.